The murder that became the oldest solved

By MAUREEN CALLAHAN NOVEMBER 16, 2014

On Sept. 11, 2008, a woman named Janet Tessier — tormented for 14 years by her mother’s deathbed confession — drafted an e-mail to the Illinois State Police. She had tried to alert authorities twice before, to no avail, and this would be her final attempt.

It read, in part:

“Sycamore, Illinois. December 1957. A 7-year-old child named Maria Ridulph vanished. Her remains were found in another county several miles away in early spring of 1958. I still believe that John Samuel Tessier from Sycamore, IL . . . was and is responsible for her death.”

John Tessier was Janet’s brother. She continued:

“I’ve given information to the person responsible for the cold case in Sycamore. I’ve done this a few times. Nothing is ever done. This is the last time I mention this to anyone . . . I’m not going to keep doing this over and over. It’s exhausting and it dredges up painful, horrible memories.”

She hit send. That e-mail would result, days later, in the reopening of 51-year-old cold case, one that would prove historic in the annals of American crime.

A horrifying crime

As recounted by Charles Lachman in his new book, “Footsteps in the Snow,” the disappearance of little Maria Ridulph became a national obsession. FBI chief J. Edgar Hoover demanded daily updates, and President Eisenhower asked to be kept in the loop. In the wake of Maria’s disappearance, 60 FBI agents descended on Sycamore.

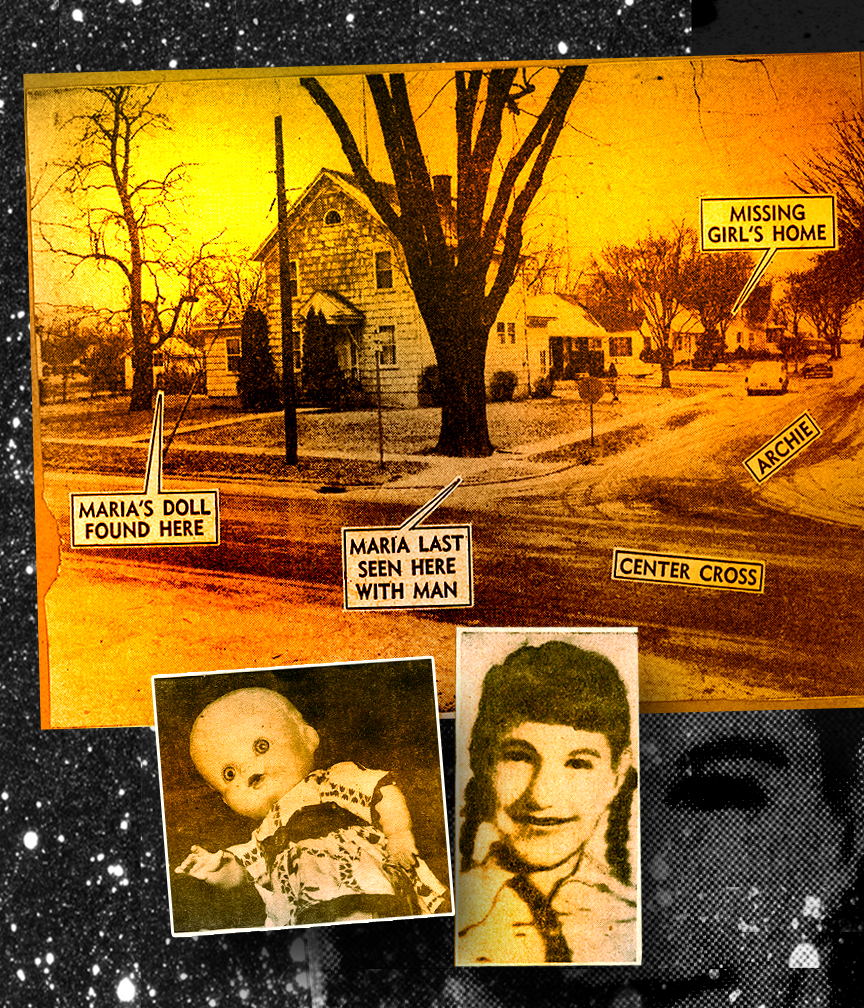

It was, in 1950s suburban America, an unthinkable crime: 7-year-old Maria, playing out in the snow with her best friend, 8-year-old Kathy Sigman, who lived five doors down. It was 6 p.m. on Dec. 3, dark and chilly, and, as Kathy recalled, suddenly there was a man in front of them on this otherwise empty street.

“Hello, little girls,” he said. “Are you having fun?”

He leaned down and asked if one of them would like a piggyback ride. Maria said yes, and Kathy watched as Johnny trotted Maria up and down the street, snow falling softly. After a minute or two, he set Maria down next to Kathy.

“My name is Johnny,” he said. “I’m 24 years old, and I’m not married.”

Then he told Maria he’d give her another piggyback ride, if only she had a dolly. Maria raced home to get one.

The man turned to Kathy. “I like you,” he said.

Kathy was stunned and confused. She didn’t really know what to say. “I like you, too,” she replied.

He put his hand on her shoulder. He asked her if she’d like to go for a walk with him, and when she said no, he asked her if she’d like something other than a piggyback ride: a bus ride? A train ride?

“I don’t want any ride,” she said.

Maria returned, cheeks flushed with cold and excitement, and she showed her doll to the man. He seemed very pleased and hoisted Maria on his back. Kathy, he said, was next, but she told him she was freezing and needed to run home for her mittens. When she returned a few minutes later, Maria and the man were gone.

Kathy raced to the Ridulph home. It was now a little before 7 p.m., and by 9 o’clock, the entire city — citizens and law enforcement alike — was on the hunt for Maria.

“If you can imagine . . . armed citizens walking the streets with shotguns and rifles and handguns tucked in their waistband, knockin’ on your door,”retired Sycamore Police Lt. Patrick Solar told CBS News. “ ‘We need to search your home — there’s a girl missing.’ They set up roadblocks on rural roads . . . They stopped every car. Searched every trunk.”

Kathy raced to the Ridulph home. It was now a little before 7 p.m., and by 9 o’clock, the entire city — citizens and law enforcement alike — was on the hunt for Maria.

“If you can imagine . . . armed citizens walking the streets with shotguns and rifles and handguns tucked in their waistband, knockin’ on your door,”retired Sycamore Police Lt. Patrick Solar told CBS News. “ ‘We need to search your home — there’s a girl missing.’ They set up roadblocks on rural roads . . . They stopped every car. Searched every trunk.”

“Don’t go anywhere near that house,” Cliffe told them.

Pam Smith, now 13, told authorities that when she was 8 years old, John Tessier approached her on the street and asked if she wanted a piggyback ride. She knew she shouldn’t say yes, but she did, and after four blocks the man wouldn’t put her down and she began crying loudly. A neighbor spotted them and called Pam’s father, who jumped in his car and sped through town until he caught up with Tessier.

He jumped out and pulled his hysterical daughter off Tessier’s back. “Never, ever go near my daughter again,” he told Tessier, and before he could complete the threat to kill him, Tessier scurried away.

An alibi, a confession

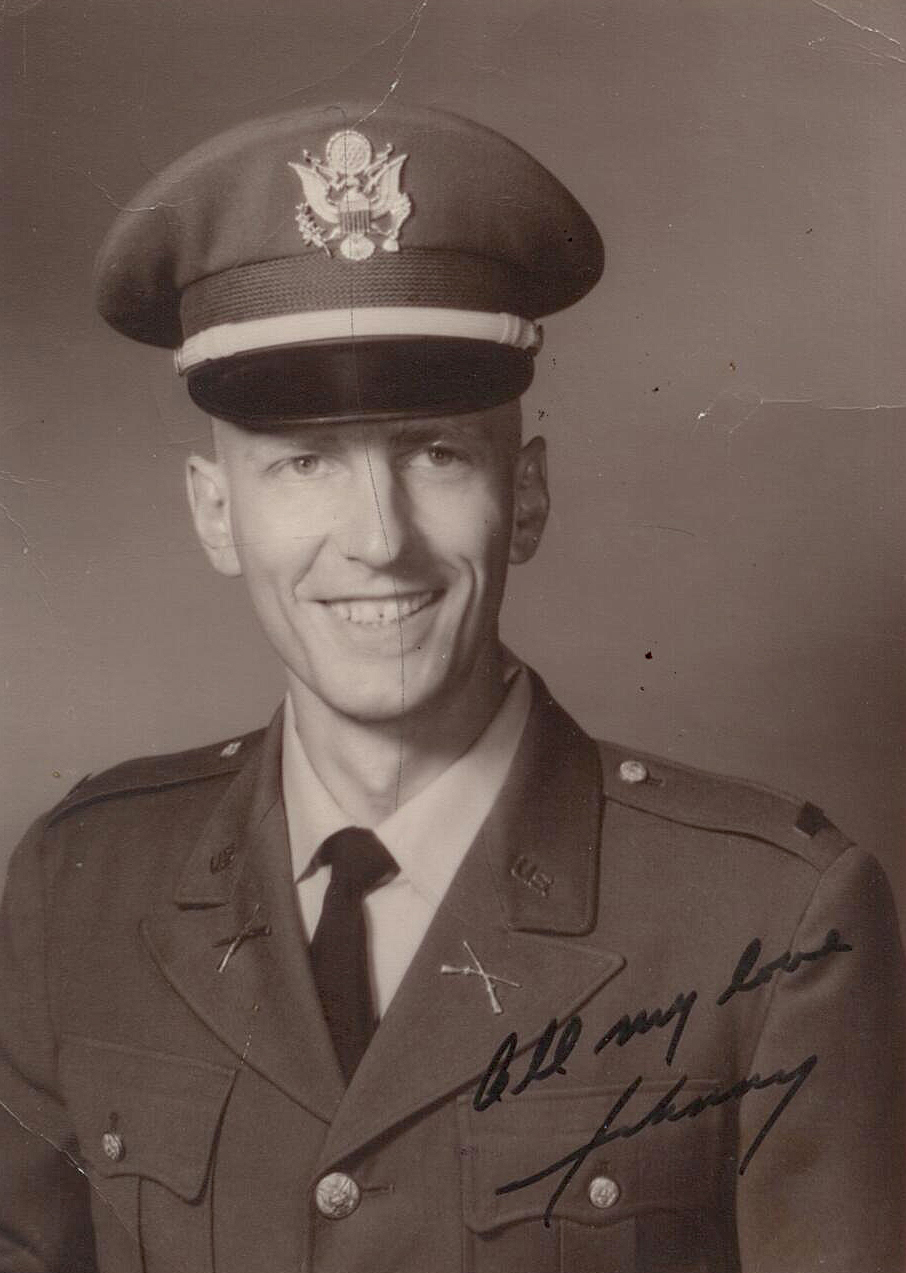

Of the 77 people who would fall under suspicion in Maria’s disappearance, John Tessier was always at the top of the list. On Dec. 9, six days after Maria went missing, the FBI brought Tessier in for interrogation.

“I know you did it,” one agent told him.

Two days after Janet Tessier sent the e-mail, she got a phone call: The case was reopened. Among the investigators was Detective Mike Ciesynski of Seattle’s homicide squad; he would be the first to knock on Tessier’s door.

Ciesynski learned that shortly after Eileen Tessier’s death, John legally changed his name to Jack McCullough. He was unaware of his mother’s confession, but his siblings had told him to stay away from the funeral, and that may have spooked him. He was living with his fourth wife, Sue, in a retirement community in Seattle.

But Tessier had an alibi. That evening, he’d been 40 miles away, enlisting in the Air Force in Rockford. His father, Ralph, said that John had called home at a little after 7 p.m., asking for a ride. His mother, Eileen, confirmed the account, and said Ralph left for Rockford, picking John up at 8 and returning at 9.

He stuck to his story, even as two FBI agents pelted him with detailed questions, even as one regularly got in his face and kept shouting, “I know you did it,” even as he was hooked up to a polygraph and passed easily.

Still, the FBI wasn’t ready to give up. On Dec. 10, they reached out to the recruiting office in Rockford. Lt. Col. Theodor Liebovich told investigators that when he saw Tessier on Dec. 4, the day after Maria’s disappearance, he seemed to be on drugs, and that he’d said he’d been rejected from the service before “because he was unstable.” As for Tessier’s claim that he was told to report to the recruiting office at 6:45 p.m. on Dec. 3, that was impossible — no office was open that late.

Tessier also encountered a Staff Sgt. Jon Oswald on Dec. 4. Oswald told investigators that he found Tessier creepy and that he’d made the unprompted remark “that it was a good thing he was not in Sycamore last night.” Then, he pulled out a little black book, in which he’d written the names and addresses of young women in Sycamore — along with their hip and bust measurements. Oswald also noticed a tiny cut on Tessier’s upper lip.

The FBI found it all extremely suspicious, but Tessier had passed his polygraph and his parents both insisted he was not in Sycamore at the time of Maria’s disappearance — that he’d phoned from Rockford, 40 miles away. Even as Kathy Sigman remained under 24-hour police protection, John Tessier was let go.

The FBI found it all extremely suspicious, but Tessier had passed his polygraph and his parents both insisted he was not in Sycamore at the time of Maria’s disappearance — that he’d phoned from Rockford, 40 miles away. Even as Kathy Sigman remained under 24-hour police protection, John Tessier was let go.

On Dec. 11, Tessier reported for training at Lackland Air Force Base. On Dec. 27, the FBI pulled all 60 agents out of Sycamore. On Saturday, April 26, 1958, a day-tripping couple stumbled upon Maria’s body off Route 20, badly decomposed, exposed to the elements and to wildlife.

The day after her body was found, the Ridulphs received a condolence letter from the Tessiers. “Your lovely little girl is well and happy in heaven with Jesus and his Blessed Mother,” they wrote. “Always remember that now you have a little saint in heaven to pray for you too.”

In the wake of Maria’s abduction and murder, both families fell apart. Maria’s brother, Chuck, was drinking heavily at 13 and an alcoholic by age 16. Maria’s parents divorced in 1963.The Tessiers, meanwhile, presided over a house of horrors. All seven children suffered abuse by both parents. John, the eldest, abused all of his siblings, and along with his father, repeatedly and brutally raped his sister Jeanne. (Tessier has denied these allegations.)

After serving in Vietnam, Tessier settled outside of Olympia, Wash., and began an ignominious civilian life. He worked as a policeman until he was arrested for statutory rape; he pled down and avoided jail time. He was constantly in debt, married four times and completely estranged from his family.

Then came that day in 1993, when John’s mother, Eileen, lay dying in a hospital bed, on a morphine drip. She yelled for her youngest daughter, Janet, who was in the room.

“Mom, I’m right here,” she said. “What’s the matter?”

“Those two little girls who disappeared,” Eileen said. “John did it. John did it.”

“Mom, are you talking about Maria?”

“Yes,” she replied. “You have to tell someone. You have to do something.”

Remember a long time ago?

It was Ciesynski who first knocked on McCullough’s door on June 17, 2011, and who arrested him 12 days later, for the murder of Maria Ridulph. Cops had no physical evidence and one lone witness, who was 8 years old at the time and now well into her 60s.

But what they did have was Eileen Tessier’s deathbed confession, which obliterated John’s alibi. They also had a litany of sexual-abuse claims against him, and Ciesynski’s seven-hour interrogation, which caught McCullough in several small lies.

McCullough went on trial for the murder on Sept. 10, 2012, in Sycamore, Ill. He waived his right to a jury; the judge would decide.

Among those who testified were Pam Long, who’d been terrified when McCullough gave her a piggyback ride at age 8; Kathy Sigman, who, in 2010, identified McCullough in a photo line-up; and three jailhouse informants who said that McCullough had confessed to each of them individually.

Among those who testified were Pam Long, who’d been terrified when McCullough gave her a piggyback ride at age 8; Kathy Sigman, who, in 2010, identified McCullough in a photo line-up; and three jailhouse informants who said that McCullough had confessed to each of them individually.

It took the judge just 25 minutes to reach a verdict: guilty. John Tessier McCullough was 73 years old, and his conviction marked the solving of the oldest cold case in American history. He was sentenced to life in prison yet maintains his innocence; on Dec. 3, he will be back in court, hoping to appeal.

It was Ciesynski who first knocked on McCullough’s door on June 17, 2011, and who arrested him 12 days later, for the murder of Maria Ridulph. Cops had no physical evidence and one lone witness, who was 8 years old at the time and now well into her 60s.

But what they did have was Eileen Tessier’s deathbed confession, which obliterated John’s alibi. They also had a litany of sexual-abuse claims against him, and Ciesynski’s seven-hour interrogation, which caught McCullough in several small lies.

McCullough went on trial for the murder on Sept. 10, 2012, in Sycamore, Ill. He waived his right to a jury; the judge would decide.

Among those who testified were Pam Long, who’d been terrified when McCullough gave her a piggyback ride at age 8; Kathy Sigman, who, in 2010, identified McCullough in a photo line-up; and three jailhouse informants who said that McCullough had confessed to each of them individually.

It took the judge just 25 minutes to reach a verdict: guilty. John Tessier McCullough was 73 years old, and his conviction marked the solving of the oldest cold case in American history. He was sentenced to life in prison yet maintains his innocence; on Dec. 3, he will be back in court, hoping to appeal.

Closing Maria’s case, Detective Ciesynski says, has had a nationwide impact on other cold cases. Over the past decade, he says, large agencies began cutting back on cold-case units due to budgetary concerns and lack of interest.

“When chiefs see the rewards of the cold cases being solved, the positive press and the positive community response, they usually . . . keep the cold-case units intact,” he tells The Post.

Recently Ciesynski — who carries pens inscribed with his personal motto, ‘Knock, knock — remember a long time ago?’ — was telling a victim’s family about the Ridulph case, that they shouldn’t give up hope. “More cases are being looked at,” he says, “and more pedophile murderers like Jack McCullough are brought to justice.”

View original article here.